The theme for TotalDairy seminar 2022 held at Stratford-on-Avon last November was ‘Future Proofing Your Dairy Business’. It attracted over 400 delegates with a strong contingent of dairy farmers. British Dairying reports.

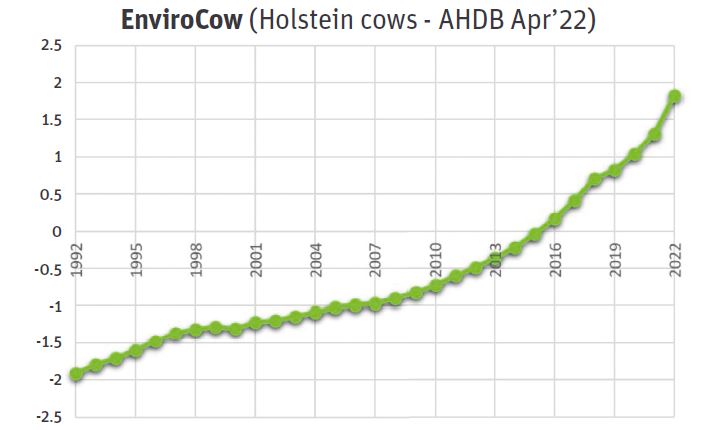

An increasing number of producers are moving their main focus for selecting bulls from Profitable Lifetime Index (PLI) to EnviroCow, according to Marco Winters from AHDB Dairy. This is so they can meet the market demands of consumers, retailers and processors and forge a sustainable future in the dairy industry.

“Genetics will play a major role in the future of the dairy industry,” said Marco. “Genetic improvements can be permanent and are a long-term solution to addressing consumer issues, particularly greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. If we want to improve the long-term sustainability of our industry, we need to tackle genetics as well as herd management and the environment we keep our cows in.”

Sustainable breeding

One of the important indices being developed for breeders is EnviroCow, which indicates more accurately the type of cow producers want to breed for their herds and meet consumer expectations, he explained. “The index is looking to the future and breeding to producing more from less inputs – a more efficient cow.”

The three elements in the calculation of EnviroCow are productivity, longevity and feed efficiency.

“Some farmers are now using this as a primary selection tool, rather than PLI, because they believe it suits their overall breeding objectives better,” Marco said. And analysis of the indices shows there is a strong correlation between PLI and EnviroCow.

The index helps reduce CO2e emissions per kg of input, and indicates how much productivity farmers can get from their cows, taking into account how long they live and how much feed they consume. “So when a consumer buys a pint of milk we can correlate it back to genetics, and say this pint of milk was produced from an environmentally friendly cow. We can reduce the GHG of that product.”

In future, it will be possible to put a GHG cost on all the traits measured for EnviroCow and put an overall carbon footprint value on the index, maintained Marco. This will allow producers to breed from the most environmentally friendly animals in their herds.

Feed efficiency is also attracting a lot of interest from breeders and the wider dairy industry, according to geneticist Prof Mike Coffey, from the University of Edinburgh. This is already included in the PLI calculation. And it is a crucial element of EnviroCow, so given a higher weighting than in PLI. “The focus on feed costs and feed efficiency has increased, and we will see a change in attitude to semen selection in future,” said Mike. Breeding companies have taken an interest in feed efficiency to give them a point of difference in semen sales.

“The feed industry has a mature approach to the impending situation and wants to help farmers reduce their feed costs. Nutritionists will want to know the herd genetics so they can help them feed more efficiently,” he suggested.

Farmers could cut feed intakes without any effect on productivity, by choosing bulls with a high Feed Advantage index and lower maintenance value. The difference between the best and worst bulls is 500kg of dry matter intake per lactation for the same level of production. Now breeders have these indices, the industry can monitor whether it is going in the right direction and hitting targets, said Marco. “I do believe genetics is one of biggest contributors to this whole debate, and is a very cost effective and powerful way of reducing GHG emissions.”

Genetic improvement reduces CO2e emissions from milk production by over 1% a year and will contribute to a 20% reduction by 2040. This is at the current rate of improvement – but if a focused effort were made then the gains would be higher. Marco urged all milk recorded herds to get a free herd genetic report from AHDB, which details the genetic potential of cows in their herd. They can then monitor their strengths and weaknesses and identify the top females to breed from.

Processors are also taking an interest in this, and one milk buyer is encouraging all of its suppliers to get a herd genetic report so it can monitor its milk pool direction.

“Genetics has a proven track record of addressing market needs,” said Marco. “The direction of travel has begun with the development and use of indices like HealthyCow, Feed Advantage and EnviroCow. EnviroCow will change as we learn more but it is a useful tool to use now.”

The growing trend in the EnviroCow index from 1992 to 2022

Tool to pinpoint mastitis source

Researchers have developed a new monitoring programme to identify the source of and prevent mastitis cases in dairy herds.

Available free to producers, the Mastitis Pattern Analysis Report is a key part of AHDB’s Mastitis Control QuarterPRO initiative and was developed by the University of Nottingham and Quality Milk Management Services.

It analyses milk recording and farm data using machine learning to produce a report every three months. This accurately identifies the source of mastitis problems and potential risks to udder health.

It is a simple system, giving farmers, farm staff, vets and advisers a way of tackling mastitis and tracking progress, said Somerset-based vet and mastitis consultant James Breen. “Long term, this is about preventing new cases of mastitis. Much of our work has focused on stopping the first case – if you don’t have a first case you cannot have a recurrence.” When identifying the source of mastitis, farmers and vets tend to be obsessed with contagious (cow to cow) transmission, neglecting the importance of environmental transmission, explained James. “You will always find pathogens if you look for them. But less than 10% of cases are contagious and over 90% will be environmental pathogens.

“Bacteriology is important for making informed decisions on treatment, but doesn’t necessarily help control mastitis or identify where the infection came from.” This requires a fuller picture, including cell counts and clinical mastitis data.” Recording mastitis cases and action taken is important, he said. “All cows that have clots in their milk should be recorded. Those treated with antibiotics are recorded but most infections cure without intervention. So it is also important to record untreated cows to help identify the infection source.”

Pinpointing infections

Using these records helps pinpoint when new infections are contracted. And the tool helps identify the source of mastitis infections without bacteriological analysis. Mastitis cases in the first 30 days after calving suggest that cows are succumbing to infections in the late lactation/dry period. After 30 days, the source is during lactation, explained James. Producers should monitor mastitis cases 30 days post-calving for the last 12 cows to calve. If infection rates are below one in 12 then mastitis control in the dry period is good. If there are more cases than this, management in late lactation and the dry period need looking at.

Case study

James outlined a case study in a high yielding 500-cow Holstein Friesian herd, housed and calving all year round and milked three times a day. Herd average cell counts were below 200,000 cells and milk sampling showed a mixed pathogen profile. Mastitis detection and recording was good and revealed that clinical mastitis rates were averaging 59 cases/100 cows per year.

A review of the system showed that this was a well-managed dairy herd, scraping slurry and bedding up several times each day, and milking cows to a strict routine in a rotary parlour with an automatic dip and flush system. Dry cows received selective dry cow therapy and were kept in early and close-up groups with plenty of space. On the face of it, this was a well-managed herd, but there were issues, said James.

Data analysis reviewed high individual cell counts, chronic cows, and low cure rates, suggesting that contagious mastitis was not a problem. Also, dry cow management was good and there was no evidence of infections during this period. “So it was clearly an environmental problem.”

There were some mastitis cases in the first 30 days of lactation, but consistently fewer than one in 12 early lactation cows had mastitis, indicating good control over the dry period. “However, after 30 days in milk the number of cases increased,” said James. “Further analysis of the data showed that there was clearly a seasonal difference, with a peak in cases during the summer months.”

Action plan

James formulated an action plan, including increasing the frequency of bedding up the early and mid-lactation groups with clean, dry sawdust, from two to three times a day day in summer, and liming bedding three times a day. In addition, the farmer gave cows access to outside yard space to reduce infection pressure in housing, and painted out roof skylights to reduce heat build-up and pathogen multiplication.

• The Mastitis Pattern Analysis tool is available free to milk producers. To sign up visit: https://cloud.remedy. farm/dashboard/#/signup-mro

This article is attributed to British Dairying Magazine. Discover more about British Dairying here.

Comments are closed.